Abstract

- Issue: “Public option” health plans, particularly as enacted in Washington State, have had difficulty meeting their goals of improving affordability for patients and reducing overall health care costs. Some states have instead created a Basic Health Program (BHP), an alternative form of coverage authorized by the Affordable Care Act that replaces marketplace coverage for residents with low incomes who are eligible for premium subsidies.

- Goals: Analyze the evolution of Washington’s public option and policy changes made in other states in response to initial rollout challenges and compare these with the policy goals and outcomes of BHPs.

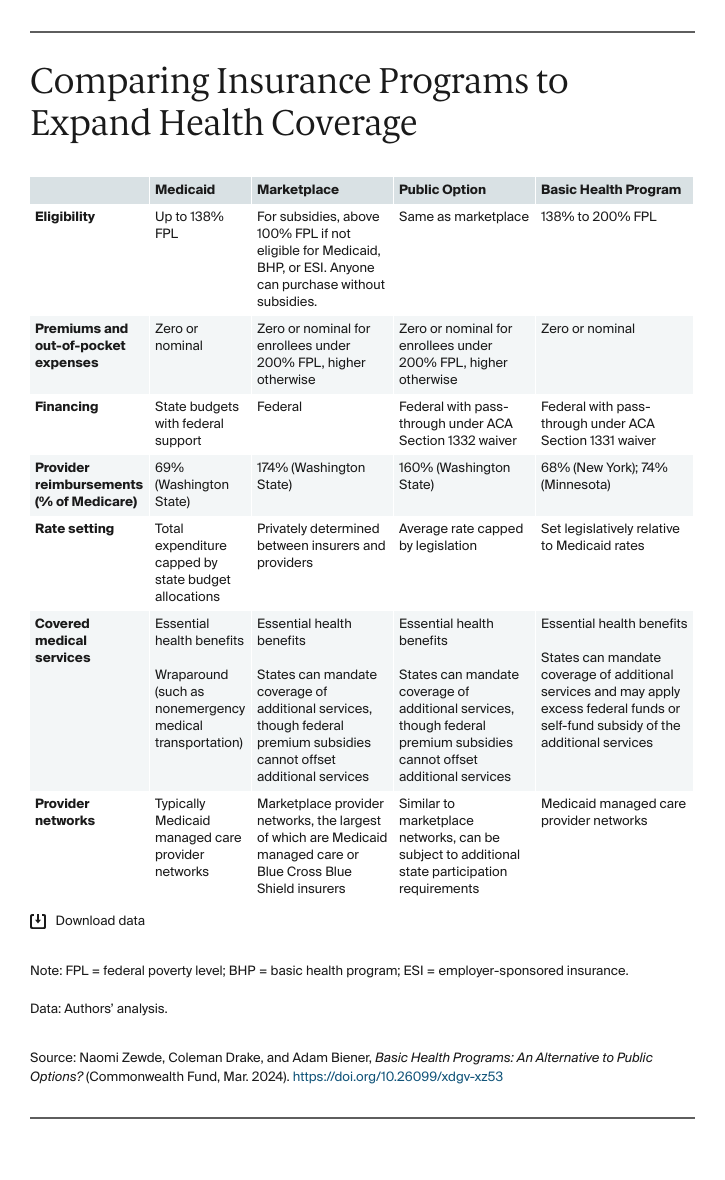

- Key Findings and Conclusion: Washington’s public option initially struggled with provider network participation and price competitiveness. Without sufficient network participation and robust enrollment, public options have few means to improve affordability or lower health care costs. BHPs are unlikely to face the same challenges. They contract with safety-net providers at Medicaid-like rates to cover all households with incomes between 138 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty level who would otherwise be eligible for marketplace subsidies. A BHP can provide robust affordability with minimal out-of-pocket spending at a low cost to states and the federal government.

Introduction

More than two decades after public option health plans were first proposed, states have begun to implement such plans in their Affordable Care Act marketplaces. The term “public option” describes an array of proposals to increase the public sector’s regulation and management of insurance products across markets. As they have been implemented so far in Washington State and Colorado, public option marketplace plans are administered by private insurers and follow state-determined guidelines for provider reimbursement rates that are lower than those of other marketplace plans.

Public options aim to use savings from reduced provider payment rates to improve premium affordability and expand benefits, in addition to lowering overall health care costs. As currently designed, however, public options’ performance has been mixed in meeting these goals.1 The rollout of Washington’s public option, for example, resulted in low enrollment and low cost savings.2 Health care providers in Washington were reluctant to join public option networks, making it difficult for public option plans to offer attractive networks or to compete on premiums with non–public option plans. Washington has since adjusted its public option regulations, effectively mandating broad physician participation without resolving disputes over payment rates.

We suggest that states consider creating a Basic Health Program (BHP) as an alternative approach to lowering premiums and out-of-pocket costs. A BHP, as defined under Section 1331 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), provides for an alternative form of coverage for people who are eligible for marketplace subsidies and have incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), or $60,000 for a family of four. Unlike a public option, a BHP does not compete with existing marketplace plans; rather, it replaces marketplace coverage for eligible state residents. States contract with insurers to offer BHPs at payment rates lower than those for marketplace plans, similar to Medicaid managed care. The ACA allows states to use these savings to increase the generosity of coverage provided by BHP plans. The only two states to have implemented BHPs, Minnesota and New York, have offered substantially more generous coverage than would otherwise be available in their marketplaces. Oregon will implement a BHP later this year.

In this issue brief, we explore a central challenge of the public option — balancing network formation against cost reduction — through Washington’s experience. We then describe how BHPs can avoid many of these challenges and achieve the affordability and cost-reduction goals often sought by policymakers pursuing public options.

Challenges Facing State Public Options

A public option plan must sufficiently cut provider payments to achieve meaningful savings, while still paying providers enough to recruit them into its network. Washington, the first state to implement a public option, tempered payment cuts prior to implementing its law. While the state initially sought reimbursement rates as low as those paid by traditional Medicare, concerns over recruiting providers to contract with the public option resulted in Washington ultimately setting public option payment rates at 160 percent of Medicare, not far below the state’s private market average of 174 percent of Medicare payment rates.3

Even with this compromise, the public option struggled to form provider networks to such an extent that approximately one-third of Washington counties had no public option plan available in 2021 and 2022.4 As a result, the public option generated little savings and attracted few enrollees. By lowering rates even more, states likely would have further undermined provider recruitment, creating a Catch-22 for policymakers caught between competing policy goals.

Premiums for Washington’s public option plans were not an attractive selling point for enrollees — they were 11 percent higher, on average, than the lowest-premium silver plan in 2021.5 Premiums are by far the most important determinant of plan selection,6 meaning enrollees were unlikely to select the public option over lower-priced private marketplace options. Ultimately, the public option attracted fewer than 1 percent of the state’s marketplace enrollees in 2021 and 3 percent in 2022.7

Attempted Remedies to Bolster Public Options

Policymakers in Washington State responded to low provider participation in public option networks with new legislation mandating that hospitals contract with at least one public option plan by 2023.8 This mandate reduced the number of counties without a public option, from 20 in 2021 to two in 2024.9 Public option plans also began to outcompete non–public option plans on premiums, becoming the lowest-cost silver plan in most counties. These changes increased enrollment: 27 percent of new enrollees and 11 percent of enrollees overall selected public option plans for 2023.

Other states have also passed laws to address the challenge of reducing health care costs with a public option. In Colorado, the second state to create a public option, state law requires that public option plans reach a 15 percent reduction in inflation-adjusted premiums by 2025, relative to premiums in 2021.10 While Colorado marketplace insurers were largely not on track to meet this goal after the first year of the program, cost savings are on track in 2024: Colorado Option plans had the lowest-premium benchmark policy in 57 of the state’s 64 counties.11 Large enrollment has followed these cost savings, with about 34 percent of Colorado marketplace enrollees selecting Colorado Option plans.12

Colorado’s success relative to Washington demonstrates that properly structuring public option regulations and implementation are critical. Nevada, taking another approach, requires that public option plans offer premiums at least 5 percent lower than competing private options when they enter the market in 2026. Anticipating challenges with recruiting provider networks, Nevada will require that insurers establish and offer public option coverage to participate in Medicaid managed care.13

While Colorado’s and Nevada’s approaches to cost savings are designed to be more robust than Washington’s, they also reveal two constraints on the ability of the public option structure to achieve improvements in the affordability of insurance and health care. Since Inflation Reduction Act subsidies already make zero-premium coverage available to many marketplace enrollees, a public option has limited ability to further improve affordability through premium reductions: becoming the cheapest plan simply replaces which zero-premium option consumers select.

To meaningfully improve access for enrollees, public options instead would need to offer lower cost sharing (such as deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments). Public options could do this via the Affordable Care Act’s pass-through provision. This waiver program, defined under Section 1332 of the law, enables states to apply any savings achieved from marketplace reforms toward additional program improvements, including reduced cost sharing.14 For example, Colorado is already using waiver funds from its reinsurance program to subsidize coverage for recent immigrants and others who are ineligible for premium subsidies, as well as to enhance existing cost-sharing subsidies for some lower-income marketplace enrollees.

As of now, the Colorado public option has achieved no-cost primary and mental health care for enrollees.15 Nevertheless, to compete on the exchanges, the plans must adhere to the ACA’s actuarial value designations. As a result, reduced cost sharing on primary care or mental health care visits roughly balances out against the out-of-pocket liabilities in the event of a serious health shock. For example, while the 2024 cost-sharing enhancements raise the actuarial value of the benchmark plan for households eligible for plans with an 87 percent actuarial value, they do so only up to 88.4 percent.16

Anticipating it would achieve a 15 percent premium reduction, Colorado became the first state to obtain a waiver for a public option.17 Additional improvements in plan generosity will depend on the public option’s success in achieving anticipated cost savings and rerouting the savings toward better plan designs. Despite progress in reducing premiums and drawing enrollment in Colorado and Washington, these plans still face the challenge of realizing enough savings to expand access to high-value, affordable coverage.

Basic Health Programs as an Alternative to Public Options

An alternative policy for expanding coverage, the Basic Health Program, or BHP, may offer greater, more straightforward progress. Because they don’t need to balance network breadth against premium savings in the same ways public options do, and because they aren’t required to conform with Affordable Care Act marketplace tier designations, BHPs can offer plans with a higher actuarial value for many lower-income enrollees.

Basic Health Programs are like public options in that they aim to use state legislative power to provide more affordable and robust coverage at a lower cost. Unlike public options, enrollment eligibility for BHPs is limited to just above the maximum income level for Medicaid, 138 percent of the federal poverty level, and replaces marketplace coverage only up to 200 percent of FPL. The ACA, which established BHPs, intended for states to create them as bridge coverage between Medicaid and marketplace coverage. Provider networks in BHPs are like those in Medicaid managed care, and the same insurers typically carry both plan types. The law also included significant financial incentives for states to provide BHP coverage, which translate into highly generous coverage for eligible enrollees.

Minnesota was the first state to establish a BHP in 2015. Known as MinnesotaCare, it covers roughly 100,000 Minnesotans, or slightly more than 2 percent of the state’s nonelderly population.18 MinnesotaCare premiums range from $0 to $28 per month. There are no deductibles; copayments range from $0 for preventive and mental health services to $250 for hospital admissions.19 By comparison, in the Colorado Option, these enrollees would pay 20 percent to 30 percent coinsurance on a hospitalization in the Colorado Option.20 New York implemented its BHP, the Essential Plan, in 2016.21 It covers approximately 1.1 million people, about 6 percent of the state’s population younger than age 65. Eligible enrollees pay $0 in premiums with similarly low levels of cost sharing. Oregon has passed legislation to implement a BHP in 2024, and several other states are considering similar laws.

Unlike public options, BHPs automatically generate large enrollment by replacing marketplace coverage for the roughly 56 percent of marketplace enrollees with incomes below 200 percent of FPL.22 They attract providers into their networks by functioning as an extension of the means-tested health care safety net, contracting with Medicaid managed care insurers accustomed to covering lower-income enrollees and recruiting networks of providers that routinely serve high volumes of patients at reimbursement rates below those paid by Medicare. BHPs bar higher-income patients from receiving more generous coverage but satisfy providers by maintaining higher reimbursement rates for the remaining privately insured. For example, provider groups resisted a recent proposal allowing any consumer to buy into Minnesota’s BHP, which would have eliminated means-testing. The providers countered with a proposal to raise the income cap instead, rather than relinquish it altogether.23

External policy changes can create further opportunities for states to transition to a BHP with greater provider support. Minnesota and New York both had expanded Medicaid eligibility prior to the ACA. They simply moved their Medicaid populations with incomes from 138 percent to 200 percent of FPL to the BHP, leaving existing provider reimbursements unchanged within that population.

Oregon will move people who were previously eligible for Medicaid under the COVID-19 public health emergency to its new BHP before enrolling others within the BHP-eligible income range. Similar to Minnesota and New York, Oregon will leave existing provider reimbursements for enrollees transitioning from Medicaid largely unchanged. The window may be closing for other states to follow. States had to unwind emergency coverage in 2023, resulting in millions losing coverage when eligibility redeterminations resumed, though many remain eligible for Medicaid despite losing coverage.24 Regardless, the lessons from these three states illustrate how changes in health coverage regimes can be used to implement BHPs that rely on established provider networks.

An important advantage of the BHP is its favorable financing structure under the ACA that enables generous coverage with a high actuarial value. Favorable financing results from Medicaid-level reimbursements to providers alongside federal subsidies tied to premiums of marketplace plans. Section 1331 of the ACA, which governs BHPs, establishes these funding rules.25 Specifically, the federal government provides states with 95 percent of the funding it otherwise would have spent to subsidize marketplace premiums for people with incomes between 138 percent and 200 percent of FPL (in other words, potential BHP enrollees). At the same time, health care costs incurred by the BHP are lower than commercial coverage by one-third or more, because BHPs pay Medicaid rather than private reimbursement rates.26

This design generates substantial savings, which are used to improve health care affordability for BHP enrollees.27 The extent of savings accruing to BHPs has grown in recent years as the federal government’s cost of providing marketplace coverage has increased. Specifically, passage of the American Rescue Plan Act and Inflation Reduction Act led to large increases in marketplace subsidies in 2021 and 2022.28 Given that the actuarial values of BHP plans exceeded 95 percent in Minnesota and New York prior to these federal policy changes,29 future states adopting BHPs could likely continue using the program’s funding to provide full or nearly full coverage to BHP enrollees.